In this article, we set out to answer something of an existential question. Is it possible to fall in love with a chatbot? Our conversation started innocently one morning with a virtual coffee and a casual comment that caught Catherine’s attention – “flirting with chatbots is a thing.” said Keith. “That’s got to be the title of your first book”, Catherine replied. So, if humans are flirting with chatbots; falling in love with a chatbot isn’t as far-fetched as you might think.

But before we get to our conclusions on this somewhat “out-there” thought, we need to walk you through some definitions, explanations and theories to frame the debate and which explore the technology (how chat bots actually work), language and sentiment (how to train your chatbot), human behaviour (emotion, trust, love etc) and organisation values – and how these, perhaps surprisingly – are inter-related and underpin digital employee experience. Oh – and not to forget the theme of this article – how a chatbot might make you want to flirt with it.

HOW DOES A CHATBOT ACTUALLY WORK?

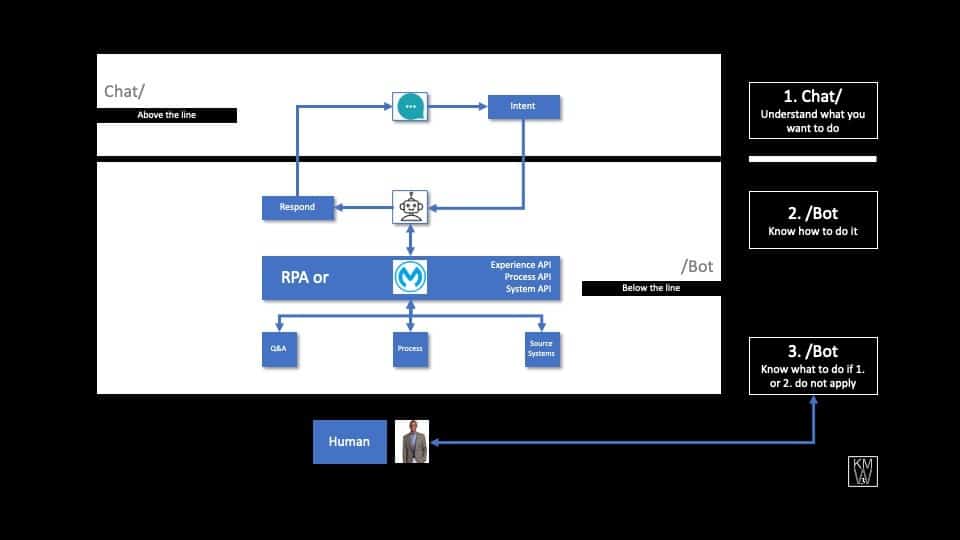

First thing to say is that the conflation of Chat and Bot into one word has led to confusion galore, and the word really does need to be divided into two words…Chat and Bot.

Bot

Let’s start with the word “bot” which is where all the work happens. It’s where either the extraction of the correct Answer to a question from a database, or the carrying out of a requested Transaction have been programmed; as well as where a meaningful response has been crafted so that it can be delivered to the User (more of this later). An “Answer” can be a response to either a General question (When is the next Public Holiday?) or a Specific one (How many days’ vacation do I have left this year?). Transactions are pretty much always specific to an individual. For example, a user might say “I want to book a 5-day vacation starting next Tuesday”. Specific Answers and Transactions both involve either APIs or Robotic Process Automation to interrogate and update core systems. It’s important to understand that none of this can happen without being programmed. The Alexa prize has proven that a 20-minute conversation with a human “is still beyond the capabilities of the current technology”.

Chat

Chat is the “understanding” element of a chatbot and uses Natural Language Processing – effectively the engine of the Artificial Intelligence at work. The Chat/Bot needs to map the words used by a user (the Utterance) to an Intent – essentially a programme which either answers a question or carries out a Transaction that the Bot has been programmed to do. It also needs to understand the user’s response to something the Bot has asked (Do you want to start your vacation on Tuesday?). Many people think that this is the easy bit (after all, they’re used to Siri understanding them!), but simple it is not, because the “chat” element of a chatbot has the understanding of a 18 month old when it is first created, which means that, much like a child, it needs to be trained. And what this requires is giving it lots of examples of Utterances (the training) and then mapping them to a pre-programmed answer or transaction. Sounds easy? But consider the different elements of language that need to be trained to be understood – there’s the business language and terminology specific to its use/application as well as small talk; to add to the complexity, language is fluid and peoples’ use of it is diverse – think about the different words and ways in which people ask the same thing; and there are cultural, geographic and regional nuances in language. And to state the blindingly obvious, if the Chat/Bot can’t understand these variations, the User Experience will range from poor to terrible (and how disappointing it would be to flirt and to get the response “I’m sorry but I don’t understand”)..

CRAFTING MEANINGFUL RESPONSES AND THE HARSH REALITY OF HUMANS

So far, so technical – but that’s not something you’re likely to want to flirt with, let alone fall in love with, right? As we’ve already pointed out – the first thing is that the chat bot’s responses also need to be programmed – surprise, surprise – the AI can’t do it by itself (despite what people might hope). That’s not to say that every response is scripted to the nth degree, but that the essence of the correct answer/response is captured and then adapted for the specific context. The good news is this means that the organisation is able to both shape the responses to reflect its values and purpose, ethical codes and how it deals with bias – and also decide on what the personality of the chatbot should be. Will it be business like, or chatty, and so on? (as an FYI, marketers often use newsreaders or cars to define brand personality….) The second thing is that you might think that users will only ask business-related questions, say please and thank you, hello and goodbye. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Anyone who has done internet dating will know that manners go out the window online. So, you need to be clear on how you would want your chatbot to respond to sexist, racist or abusive interactions with employees. Believe us, your colleagues will test this out, and how your chatbot responds will impact how they perceive the values of your organisation. Enter the script writer, the master of dialogue and refined conversation. No, we’re serious – the fancy name is Conversational Architect and yes, this role/person really does exist. The role of the script writer is to write the responses to Users’ utterances in a way which reflects the values and ethics of the organisation and in the voice of the chatbot’s personality. If all goes well, the chatbot emerges as a virtual agent representing the organisation with the ability to understand human language and the user’s intent, and to respond correctly, appropriately and with a human voice. So, if a person asks the bot to go on a date (which in technical terms is just another Utterance), the bot better be able to recognize it as such (just another intent) and have a reply ready – one which is in line with organisational values, the ‘bot personality’ and engenders a positive emotional response. You have to decide if you want your chatbot to respond with “Sorry I’m not that kind of Bot” or with “I’m flattered you ask, but I’m so busy in my role as a Digital Assistant that I don’t have time for dates” or even “Absolutely not – you know that we don’t condone workplace relationships”. Whichever option you chose (or indeed any another) says a lot about your organisation! Not only that, it’s one of the things which defines how users react emotionally.

Can a chatbot engender an emotion?

As sentient beings, humans seek meaning in everything we do, indeed the quest for meaning informs how we communicate. From birth we learn to interpret a system of complex signalling from those around us in the form of verbal and non-verbal cues, based upon a set of common beliefs and values. Communication is physics (sound waves) + biology (neurological activity) + culture (signalling or codes). Effective communication requires emotional self-awareness and empathy – the ability to walk in someone else’s shoes; these two alone comprise 15 traits of what Daniel Goleman has called emotional intelligence. But AI famously has no Emotional Intelligence, which is why the Conversational Architect is so important. Until great advances have been made, human programming will have to suffice. The $60 million-dollar question is “can you programme the chatbot to show empathy – to respond like a human does and engender trust?”. The jury’s out on this one. Some say a categorical no. Others that a great Conversational Architect can craft responses that are personal and almost human. Another view is that you can get somewhere in between with contextual responses; so, when the human first meets the chatbot it says, “Nice to meet you Catherine”, but after a few interactions says “Nice to see you again Catherine. How are you?”. This begins to reflect a real human interaction; it changes over time, shows human warmth and makes the human feel good – and possibly engenders trust and liking?

The psychology of trust

The psychology of trust involves both a complex neural process and an emotional dimension. When we trust someone, we experience feelings of confidence and security. Oxytocin, otherwise known as the LOVE hormone, appears to have relationship-enhancing effects, including trust, empathy and fidelity. It’s a naturally occurring hormone that is present when women give birth. When you are attracted to another person, your brain releases dopamine, your serotonin levels rise, and oxytocin is produced. This causes you to feel a surge of positive emotion. Its role is, of course, to promote attachment. In his book Trust Factors, Paul J Zak researches the impact of key behaviours on Trust, he does this by measuring levels of Oxytocin in the blood. He discovers that the behaviour that has the single biggest impact on trust is CARE. When we show care to another human being, we show concern for them. A true sense of belonging is therefore based upon care for and obligation to others. But how do we engender trust with a chatbot and make users believe that it cares… Some ideas here might include; firstly, the bot’s personality – does it have a personality that we like? Secondly, as previously mentioned, contextual conversation. Much like establishing a relationship with a human; these common niceties engender warm feelings of ‘how lovely, the bot remembers me’.

The science of conversation

So, what does the future hold? Will chatbots be able to hold more personal and or personalised conversations? In her book, “Talk, the science of conversation” Elizabeth Stokoe describes human conversation as highly organised. “We are quite unaware of how systematic our talk is and how different words lead to different outcomes.” The science of conversation analysis began in the 1960’s and it certainly feels as if, with the development of AI, neural networks and machine learning the next decade could represent its coming of age. However, there currently remain very real limits to chatbot technology. Conversational Analysis is not Conversation creation. The Turing Test is a long way from being passed. In reality, the Chat/Bot has to be trained with data in order to “understand” what the user means. At a very real level, the emotions of sarcasm, anger, frustration, excitement, joy are all irrelevant to it – the user just uses words or phrases which it has to be trained to recognise. But through the design of its responses in terms of content and style, the Bot can operate at the small talk level and can, for example, meet farcical moments head on. Critically, the response to “I don’t know what you are #§@&%*! talking about”, if well-crafted, allows the Bot to reflect the voice of the organisation, become the arbiter of trust, honesty and transparency. This is where chatbot strategy and design gets interesting because it crosses over into the human domain of relationships, “social interaction” or what Stokoe refers to as “natural action processing.” However, this only scratches the surface of the complexity of human conversation. This comes into sharp focus when looking at the work of conversation analysts, as Stokoe illustrates – “we include detail about pace, prosody, intonation, overlap, interruption, repetition, repair, interpolated laughter, the tiniest of incipient sobs, and much, much more.”

SO, WHAT ABOUT FLIRTING WITH A CHATBOT?

Flirting or coquetry is a social and sexual behaviour involving spoken or written communication, as well as body language, by one person to another, either to suggest interest in a deeper relationship with the other person, or if done playfully, for amusement. To play at love perhaps. (ref. Flirting – Wikipedia) What is certain is that, as users begin to trust and like a chatbot, they may begin to push boundaries and start asking personal questions – something they might not do if they were talking to a human. At one level this is a measure of success for the bot. But the success will be lost if the bot’s only response to flirting is “I’m sorry, I don’t understand”.

CONCLUSION

We’ve learnt that it is possible to train a chatbot to understand language, intent and sentiment – and to programme it to respond accordingly. We also know that appropriate responses must take into account the cultural values of the organisation and to be able to deal with potential negative or inappropriate sentiment on the part of the user. We also know that a well-crafted chatbot will have a distinct personality and be able to personalise human interactions. This being the case, an interaction between a human and an AI will elicit neurological activity in the human brain and the release of certain chemicals. It is entirely logical that said human might act out “flirtatious” behaviours…. but to fall in love? Assuming that the AI is trained to meet our emotional need for safety, belonging and significance; and if crowdsourcing of utterances means a database grows to such a size it matches the complexity and depth of the human language across the globe, will it be possible to fall in love with a chatbot? We think not, but flirting with a chatbot, we can see that in our future. Can you?

TL;DR

People don’t know how Chatbots actually work but get them right and they not only understand what is being said to them, but also can be programmed to respond in an insightful way which not only implies a personality but also represents the values of the company. However, users may not only ask business-related questions but may also become personal. You need to know how to deal with that.

About the Authors

Keith Williams is ex-HR Services Technology Director @ Unilever and is a Director at KMW3. He uses his global experience to help organisations with HR Digital Transformation, digital Employee Experience and conversational Chatbots.

You can contact Keith at keith.williams@kmw3.com or +44 (0)7876 252278

Catherine de la Poer is a leadership coach and founder at Halcyon Coaching, where the focus is to create more resilient and agile individuals, teams and organisations. Emotional Intelligence forms the centrepiece of her coaching approach.

RELATED INSIGHTS

Let’s talk